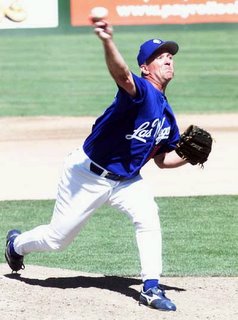

Mike Fetters

Michael Lee Fetters did not like to mix it up.

Michael Lee Fetters did not like to mix it up.Prior to each pitch, the big, burly right-hander went through the same eaxct routine.

As Fetters would go into the stretch, he would take a long, deep breath, bringing his hands slowly to his belt. He then would snap his head violently toward homeplate and glare at the batter before hurling the ball toward homeplate.

He never deviated from this practice.

His wild man antics reminded some baseball fans of Al "The Mad Hungarian" Hrabosky.

However, unlike Hrabosky, Fetters wasn't trying to put on a show to entertain the fans. Nor, was he trying to scare major league batters.

"I didn't do it for publicity or to intimidate hitters," Fetters explained shortly after his playing days were over. "They're major leaguers and they aren't intimidated by things like that. I did it because I had an asthma condition." Fetters noted, "It's hard to pitch to a batter when the bases are loaded in the bottom of the ninth inning and you can't breathe."[1]

Nevertheless, whenever Fetters came into the game it was baseball theater at its best.

And the fans loved it.

A southern California native, Fetters was selected by the California Angels with the 27th overall pick in the first round of the 1986 amateur draft. He played in the big leagues for 16 seasons with eight different teams, including the Dodgers in 2000 and 2001.

Fetters had his best season in 1996 with the Milwaukee Brewers, when he posted a 3-3 record with a 3.38 earned run average while registering 32 saves.

--------------------

[1] Walters, Jim. "Fetters Turning Heads Once Again." <http://www.azcentral.com/sports/columns/articles/0225cr-spcolumn0225Z6.html>, Feb. 25, 2006.

Jesus Maria “Pepe” [Andujar] Frias

Jesus Maria “Pepe” [Andujar] Frias